As the editorial specialist for LearningWorks for Kids, I’m no stranger to the idea of using video games and technology as tools for teaching children. At LW4K, we research and write a lot about the way games like Minecraft can be used at home and in school to help build executive functions and establish the digital literacy and citizenship necessary for succeeding in the 21st century. But lately, my Google Alerts have been setting my email ablaze. The buzz surrounding the use of video games and technology in the classroom is growing louder.

There’s exciting stuff happening, like the $2 million grant from the National Science Foundation for a research project that will examine the effectiveness of Minecraft for teaching math and computer science skills to kids in rural Maine. Equally exciting is the announcement that the free virtual reality kits Google plans to bring to students across the globe this school year have just landed in two Chicago elementaries. And a quick search will bring up myriad other local and national stories covering this “trend”. (I use quotations because the word “trend” undermines what I believe to be true: games are here to stay.)

We tend to hear about technology in education primarily in relation to STEM, and video games have been much slower to break into higher education curricula. So I really sat up and took notice of Jessica Conditt’s recent article on Engadget, in which she tackles the conundrum video games present to the traditional art college. She argues that video games are a valid medium, and that film encountered the same kind of resistance once upon a time. Her point, and it’s a good one—and relevant to the work we do at LW4K—is that stigma still plays a large part in how video games and technology are perceived and received.

[cjphs_content_placeholder id=”73595″ random=”no” ]So it’s not surprising to read pieces like the one written by Pamela J. Hobart for Bustle. Hobart references Conditt’s article, but brushes past the discussion of video games as art form and increasingly accepted learning tool to paint them as a likely waste of time and potential source of grade inflation. “You also can’t just expect any old video game to serve an educational purpose,” Hobart writes, “Without careful input from and collaboration with seasoned educators, even the most beautiful and engaging game will remain just that—more entertainment than education.”

(Clockwise from left) Perfection, Zoo Rush, Elude, and Depression Quest are games that break the mold to take on societal health issues

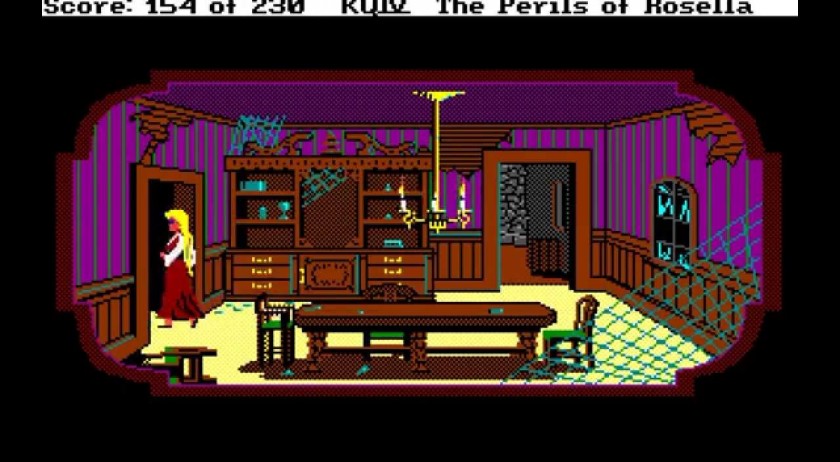

I respectfully disagree. At least about the idea that the input and collaboration from educators and other professionals always needs to happen in the development phase rather than with the end users (the players). Hobart is right, of course, if you are expecting to learn from the content of a video game alone. And don’t get me wrong, there are some games out there that have broken the mold to provide instruction in subjects from classical history to business strategy and opportunities for perspective taking on societal health issues like sickle cell anemia, eating disorders, and depression.

The truth of the matter is, whether at the elementary or college level, learning isn’t just about walking away with a headful of facts, and even the most interesting textbook isn’t all that effective unless its readers are being challenged to engage with the material. Advocates of games as learning tools do not recommend sitting down to an entire day of thoughtlessly playing The Sims. Even though we exercise lots of skills when we game, we don’t benefit very much from that exercise unless we make a conscious effort to translate it to real world practice.

As well, we need to give credit to educators, because just as films and books are carefully selected for inclusion in a curriculum, so are the video games that are now being assigned to students. That being said, with the right guidance, even a game that seems to have little educational value—be it World of Warcraft, Call of Duty, or Bejeweled—can be a powerful teaching tool—one that promotes organization, planning, focus, self-awareness, self-control, critical thinking, problem solving, and other important real-world skills. And as for the substitute teacher who might encourage a day of game play, I’m not sure this differs much from the sub who might pop in a movie, which has more to do with the person than the medium.

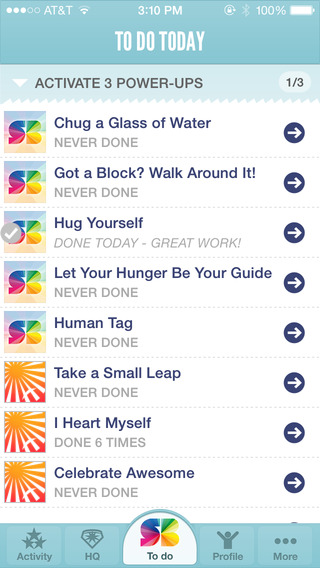

Yes, there is still more research to be done, and that’s largely due to the the fact that games and technology are advancing so quickly that it’s difficult for science to keep up. That being said, many researchers have already found benefits in video game play, and the fact that there are apps and games like Cogmed Working Memory, BrainHQ, and Akili Interactive’s upcoming Project: Evo that are backed by many, many peer-reviewed research studies speaks volumes. There’s even a self-help method, with an accompanying app and book, based on living life as if it were a video game, and it’s getting a lot of positive attention. Whether or not all experts are on board, the overwhelming consensus is that gamification is working. More and more schools (corporations, too, for that matter) are utilizing games because they see the results—they teach important skills and engage people in learning.

I’ve been playing video games for approximately 30 years, a fact that might serve to explain my passion. Now I’m a new mom armed with all sorts of new knowledge that makes me eager for my baby to be coordinated enough to hold a game controller (and to not fling pureed peas all over the kitchen). While dissenters might caution you to protect your investment in your child’s education and steer clear of video games, I say that if your kid’s college is flexible and forward-thinking enough to embrace games and technology, she’s in the right place. And as she prepares for her future in the digital age, she’ll also be taking part in history.