Kids with slow processing speed frequently need emotional support and understanding, but sometimes the best help they can get is more time to complete tasks. And this is not just about finishing classroom work. Parents frequently ask me about slow processing speed and the SAT — what if their child runs out of time?

A little extra time to finish a routine weekly quiz or a test goes a long way in helping these kids show what they know. The same is true for high stakes testing such as the SAT, ACT, PSAT, and GRE, where achieving a lower score because an individual did not have enough time to get through the test can have steep consequences for a child’s future. Being unable to finish a large portion of the, SAT can result in low scores and limited options for college.

Not all kids who struggle to complete a high-stakes test have slow processing. Some will find questions they cannot answer correctly, no matter how much time they are given to complete a test. After all, many of the items are designed to be extremely challenging in order to differentiate among students.

The premise of providing extra time on high stakes testing to kids with slow processing speed, Learning Disabilities, ADHD, and other disabilities is based upon the assumption that this allows these students to work to their potential, whereas extra time will not make any discernible difference for typical students who simply do not know the material. It’s an argument that seems to hold mostly true for the verbal sections of the SAT.

Interestingly, a study by the College Board (which administers the SAT) indicates that examiness with disabilities show slightly more improvement than typical examinees when given extra time (1.5X), but that the biggest beneficiaries of extra time is for high and medium ability examinees (with or without disabilities) on the math portion of the testing. The study also found that double time was actually less helpful than 1.5 time and that having breaks between testing sections benefited all examinees.

It has traditionally been difficult to receive additional time for high-stakes testing. Part of the caution on the part of the College Board, Educational Testing Service (ETS), and the ACT was due to socioeconomic factors making it more likely that students from wealthy families were getting advantages based upon accessibility more than need.

A study conducted in California in 2000, found that “white students were over-represented by 45%, students coming from families whose incomes exceed $100,000 were over-represented by 139%, and students from private schools were over-represented by 100%.” Essentially, this suggested that parents who could afford to get their kids evaluated and diagnosed with a disability could secure an advantage for their kids in high stakes testing. While undoubtedly many of these kids have legitimate learning issues or slow processing speed, my observations suggest that there are also some driven parents who may be pushing the limits for their kids.

Now that the testing companies are using test results that compare students’ psychological assessment results to those of average students (rather than the discrepancy model, which compared students’ varying test scores to each other), it is easier to make consistent judgements. In other words, students whose IQ testing might suggest brilliance but whose reading ability is only average would likely no longer qualify for accommodations, while those with average cognitive abilities but below average reading fluency would be more likely to qualify.

In this case, poor reading fluency is seen as a functional impairment. Unfortunately, this approach may disadvantage some very capable students who may have achieved average or low average scores on measures of processing speed through compensatory strategies but whose productivity and timed test scores are still far below their potential.

Slow processing speed in isolation may not qualify students for accommodations in high stakes testing unless there is a history of documenting this difficulty and evidence that their schools have taken this seriously in the past. This is one of the reasons to have children seen by a child clinical psychologist or a neuropsychologist who has an expertise in this area. In my work as a child clinical psychologist the most common impact of slow processing speed is on the amount of time it takes to complete homework and exams, often starting in first grade.

Kids with slow processing report that they are always among the last to finish their classwork or to turn in their tests and often have a clear recollection of this dating back into early elementary school. Their parents frequently describe homework as an ordeal that takes hours rather than minutes. Ensuring that there are records of slow processing speed through report cards, classroom accommodations, and school interventions such as a 504 plan or an IEP can help when asking for high stakes testing accommodations..

It is important to act early if you are considering college for a middle or high school child whom you suspect of having slow processing speed. Evaluation of the child to obtain objective measures to assess these concerns and working with the child’s school to create a set of appropriate accommodations are essential. Meanwhile, keep working on strategies to improve processing speed, including the use of technology to support slow processing speed. Creating a paper trail of addressing this concern can help in obtaining extra time for high stakes testing. For elementary school children with slow processing speed, the sooner you get some basic accommodations in place, the stronger your child’s case will be to have extra time when it comes to taking the SAT or ACT.

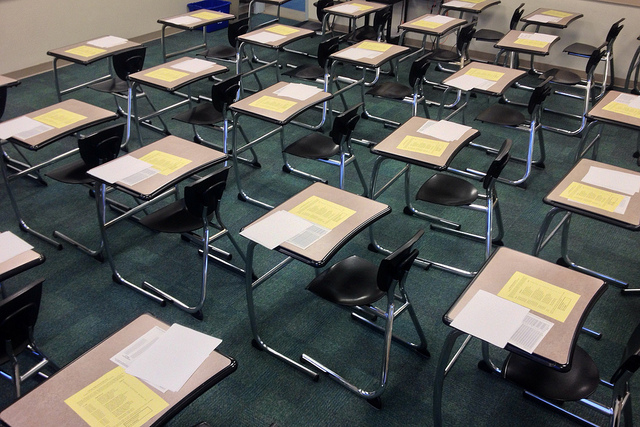

Featured image: Flickr user Eric E. Castro