In today’s classrooms, slow processing speed is being increasingly identified as a major cause of poor academic performance. For many capable students who are motivated to do well, slow processing speed is an obstacle that prevents them from keeping up with their peers. Slow processing speed is not a new concern, though our perception today of what is “slow” may well be influenced by the demands of the digital age.

Students with slow processing speed tend to work more deliberately and often require extra time to master academic material. It’s common for these kids to have difficulty completing tests and exams in a timely manner. Many students with slow processing speed benefit from school-based accommodations, such as 504 plans, that allow them additional time to complete classwork and tests. It may also be necessary to relax strictures around written tasks or allow them to borrow notes from a peer or access a PowerPoint from a teacher.

In order to qualify for these accommodations, neuropsychological evaluations are often requested in order to provide evidence of slow processing speed. However, professionals measure processing speed in a variety of ways, and many parents and educators are unclear about what these neuropsychological tests measure.

It’s common for parents to have an “aha” moment after a child’s slow processing speed is confirmed by a professional, when suddenly many of the issues present since early childhood make sense. They always took much longer than their siblings to finish their dinner, were always late when getting ready to go somewhere, and tend to be slow moving in completing chores or even in a fun activity such as playing with LEGOs or drawing a picture.

Neuropsychological testing consists of a variety of tests that examine how a child processes verbal and visual information. Psychologists are able to assess the speed and accuracy of information intake, how a child manages that information in the brain, and how quickly and accurately a child is able to produce some form of output.

The following are common methods for how we measure processing speed.

The Wechsler Scales (WPPSI-4, WISC-V, WAIS-4) – All of these tests have an index that measures the ability to efficiently scan and understand visual information and complete a task with that data. The Coding subtest may also provide feedback about dysgraphia and poor handwriting. The Naming subtests also measure naming speed, closely associated with processing capacity.

NEPSY 2 (The Speeded Naming Test) – This test measures the pace at which a child is able to name shapes, colors, letters, and numbers.

WIAT-3 – This educational test measures reading, writing, and mathematical fluency.

Woodcock Johnson III (Tests of Achievement) and Woodcock-Johnson IV – Both of these tests assess cognitive and academic fluency with a variety of scales.

RAN/RAS (Rapid Automatized Naming & Alternating Stimulus Tests) – This test requires rapid naming of shapes, letters, numbers, and colors.

Stroop or Color Word Naming Test – These similar tests add a cognitive flexibility component to measuring processing speed.

When a child is identified as having slow processing speed, most interventions focus on making accommodations. However, there is increasing evidence that technologies — action video games, for example — can improve the speed of visual processing. We encourage you to check out some of the games and apps we’ve written about that can help your child practice time management skills. We also have many articles that address this issue on our blog.

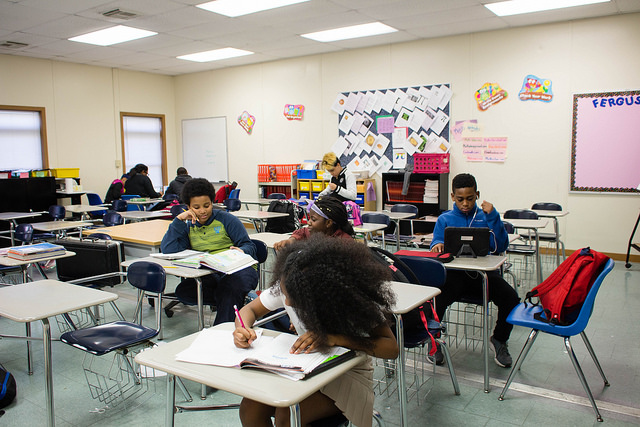

Featured image: Flickr user Paige Bollman